I was born in a liberated Bangladesh, a brand new country carrying numerous unprocessed emotions, pain and loss covered by a deep sense of nationalism. When we were growing up in the 80s, the true freedom fighters were hiding their faces in the depth of their palms. Our parents were searching for elements to pass on to their children, objects and visions which were a bit more than war wounds. The Indian filmmaker and writer Satyajit Ray was such element that we received as prize inheritance.

As a child I categorised my peers into two groups. Those who had watched the children's films by Satyajit, mainly Hirok Rajar Deshe and Gopi Gain Bagha Bain, and those who had not. As a second grader, he was the guide who navigated my practical riddles. Ray dictated whether I could relate to someone and possibly become friends.

Those films of Satyajit were shown in Dhaka at the Indian High Commission; later, they were available in video cassettes, the soundtracks were played numerous times in some households, and the rhythmic dialogues were memorised like poetry. We believed in Satyajit, he depicted the way many wanted to see the world, with long frames, pauses and the most suitable background score.

But what made my parents' generation seek Satyajit? It all began with his film Pather Panchali (Song of the Little Road) which is still considered a masterpiece for modern cinema worldwide. The film was based on a novel by Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay, written in 1929. Pather Panchali was screened at the New York's Museum of Modern Art in 1955 and received international fame and critical acclaim. It was later screened in India where South Asian eyes appreciated what the global art scene had already bestowed great recognition to.

Satyajit's Pather Panchali was produced by the Government of West Bengal. Ray filmed it over three years, with many interruptions due to funding problems. At the last stretch Ray took the film to the then Chief Minister of West Bengal, Bidhan Chandra Roy, and over a private screening of the incomplete film the Chief Minister agreed to fund the deficit.

We often don't talk about the private/public supporting hands which push forward artists and art to higher platforms, the enabling factors which are essential for the artistic process. I can't imagine a world without Satyajit and maybe there would be no Pather Panchali if there was no Chief Minister Bidhan Chandra Roy, who must have seen a glimpse of something spectacular in that unfinished reel and helped Ray with the last bit of financing.

In Bangladesh, my generation grew up carrying second-hand war experiences, figuring out what we could call our own. With such close ties with India and Pakistan, what was it to be a Bangladeshi? Who we were before 1971, and how much of the history we could claim as ours was our collective dilemma. Intellectuals were mass murdered two days before Bangladesh was liberated, the country went through a brain drain and art was everywhere yet nowhere. The artists who survived and witnessed the struggles of Bengal pre- and post liberation kept at their work. Some we had not heard of in popular mediums, not until they died.

![2015-12-14-1450104994-170248-FirstPlantationFirstPlantation1976OilonCanvasSMSultanCourtesyBangladeshShilpakalaAcademy.jpg]()

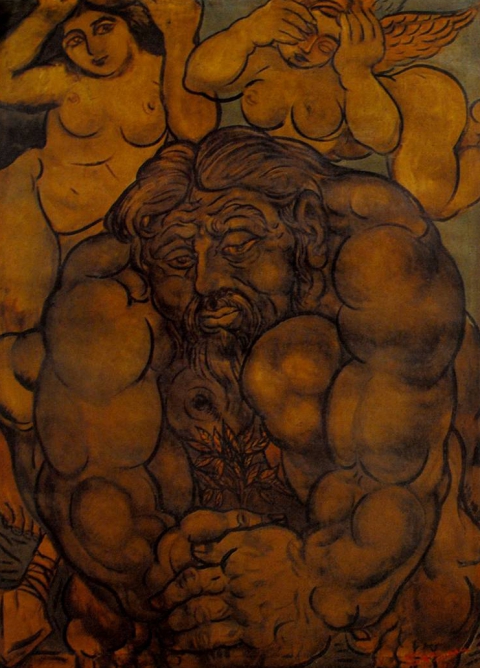

First Plantation, 1976, Oil on Canvas, SM Sultan, Courtesy Bangladesh Shilpakala Academy

Among them is artist SM Sultan, one of the pioneers of Bangladesh's modernism. A good part of Sultan's life was spent in India and Pakistan. It is rumoured that some of Sultan's pieces can still be found sitting behind the sofas of collectors in Karachi and Lahore (mainly due to Sultan's own indifference towards preserving his work). The exhibitions of his work in Karachi in the late 1940s brought him to the greater public eye. And then, Sultan was the official selection by the Government of Karachi in early 1950s, giving him the opportunity to exhibit his work at the Institute of International Education in New York, as well as Boston and Washington DC. I wonder what that journey meant to Sultan, because his next big move grounded him as an artist, moving him to a new phase with a decision to migrate to a village in Norail, Bangladesh in 1953. In that village, he spent many years depicting the inner strength of the common people of Bengal. Those pieces are of high value now, in places beyond South Asia.

So here we have two fathers of modernism from South Asia, Satyajit and Sultan who stepped a little further with the support of the government. First they caught the eyes of a few individuals who saw the higher value of their work, and then came further opportunities of exposure leading them to find greater voices, or should I say easels, colours and frames.

But where are we today in terms of art, artists and the support of public/private sectors? The modern world has allowed more cash flow into bodies which recognise the importance of art and artists. And in a country like Bangladesh, we are in a great need for such promoting hands. The government of Bangladesh has been facing more pressing issues than setting up a stronger platform for the arts with an updated infrastructure which supports the growth of artists. It has largely been an individual journey for artists in South Asia. Many have joined the advertising industry, or worse, changed careers completely to make ends meet.

As a child I categorised my peers into two groups. Those who had watched the children's films by Satyajit, mainly Hirok Rajar Deshe and Gopi Gain Bagha Bain, and those who had not. As a second grader, he was the guide who navigated my practical riddles. Ray dictated whether I could relate to someone and possibly become friends.

As a child I categorised my peers into two groups. Those who had watched the children's films by Satyajit [Ray]... and those who had not.

Those films of Satyajit were shown in Dhaka at the Indian High Commission; later, they were available in video cassettes, the soundtracks were played numerous times in some households, and the rhythmic dialogues were memorised like poetry. We believed in Satyajit, he depicted the way many wanted to see the world, with long frames, pauses and the most suitable background score.

But what made my parents' generation seek Satyajit? It all began with his film Pather Panchali (Song of the Little Road) which is still considered a masterpiece for modern cinema worldwide. The film was based on a novel by Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay, written in 1929. Pather Panchali was screened at the New York's Museum of Modern Art in 1955 and received international fame and critical acclaim. It was later screened in India where South Asian eyes appreciated what the global art scene had already bestowed great recognition to.

Satyajit's Pather Panchali was produced by the Government of West Bengal. Ray filmed it over three years, with many interruptions due to funding problems. At the last stretch Ray took the film to the then Chief Minister of West Bengal, Bidhan Chandra Roy, and over a private screening of the incomplete film the Chief Minister agreed to fund the deficit.

We often don't talk about the private/public supporting hands which push forward artists and art to higher platforms, the enabling factors which are essential for the artistic process. I can't imagine a world without Satyajit and maybe there would be no Pather Panchali if there was no Chief Minister Bidhan Chandra Roy, who must have seen a glimpse of something spectacular in that unfinished reel and helped Ray with the last bit of financing.

In Bangladesh, my generation grew up carrying second-hand war experiences, figuring out what we could call our own. With such close ties with India and Pakistan, what was it to be a Bangladeshi? Who we were before 1971, and how much of the history we could claim as ours was our collective dilemma. Intellectuals were mass murdered two days before Bangladesh was liberated, the country went through a brain drain and art was everywhere yet nowhere. The artists who survived and witnessed the struggles of Bengal pre- and post liberation kept at their work. Some we had not heard of in popular mediums, not until they died.

First Plantation, 1976, Oil on Canvas, SM Sultan, Courtesy Bangladesh Shilpakala Academy

Among them is artist SM Sultan, one of the pioneers of Bangladesh's modernism. A good part of Sultan's life was spent in India and Pakistan. It is rumoured that some of Sultan's pieces can still be found sitting behind the sofas of collectors in Karachi and Lahore (mainly due to Sultan's own indifference towards preserving his work). The exhibitions of his work in Karachi in the late 1940s brought him to the greater public eye. And then, Sultan was the official selection by the Government of Karachi in early 1950s, giving him the opportunity to exhibit his work at the Institute of International Education in New York, as well as Boston and Washington DC. I wonder what that journey meant to Sultan, because his next big move grounded him as an artist, moving him to a new phase with a decision to migrate to a village in Norail, Bangladesh in 1953. In that village, he spent many years depicting the inner strength of the common people of Bengal. Those pieces are of high value now, in places beyond South Asia.

So here we have two fathers of modernism from South Asia, Satyajit and Sultan who stepped a little further with the support of the government. First they caught the eyes of a few individuals who saw the higher value of their work, and then came further opportunities of exposure leading them to find greater voices, or should I say easels, colours and frames.

But where are we today in terms of art, artists and the support of public/private sectors? The modern world has allowed more cash flow into bodies which recognise the importance of art and artists. And in a country like Bangladesh, we are in a great need for such promoting hands. The government of Bangladesh has been facing more pressing issues than setting up a stronger platform for the arts with an updated infrastructure which supports the growth of artists. It has largely been an individual journey for artists in South Asia. Many have joined the advertising industry, or worse, changed careers completely to make ends meet.

Speaking to Lipi I heard about her evolution as an artist and the different inspirations and supporters of her work during the span of her life. In the earlier days, her husband Mahbubur Rahman, also an artist, played a key role in supporting her prolific mind and work. There were others who came in and out of the space, some collaborators, some foreign supports. Lipi had been working in the art space for quite some time, when she met the couple Nadia and Rajeeb Samdani, of the renowned Dhaka Art Summit. Nadia and Rajeeb belong to our post-71 generation and they are best known for their organised search of South Asian art, as well as branding South Asia with the art (specifically contemporary) label in recent years. But to us Bangladeshis, it is the Dhaka Art Summit and the initiatives of the Samdani Art Foundation which set Nadia and Rajeeb apart. Recently, ArtNews also recognised these initiatives of the Samdanis and placed them on their annual list of top collectors. It is also impressive that this young couple are members of the Tate International Council, influencing the global art scene and not just South Asia.

In Bangladesh, we do not have any museum of contemporary art, or educational institutions shedding light on young artists' paths.

I first got to know Nadia and Rajeeb at the Dhaka Art Summit 2014 where I was amongst the 70,000 visitors. I later did a profile of the couple for a Mumbai-based magazine (Indian Quarterly) and discovered that projects from the 2014 Dhaka Art Summit later travelled to the Berlin Biennale, the Queens Museum, Kochi-Muziris Biennale, the Kunsthalle Basel, the San Jose Museum of Art, and that a project that was commissioned for the 2016 Dhaka Art Summit will debut at the 8th Asia Pacific Triennial in Brisbane this November. Looking further into the past, the work that Tayeba Begum Lipi exhibited at the Guggenheim was commissioned for the first Dhaka Art Summit in 2012. These works of tremendous quality were all born in Bangladesh by artists who were nurtured in the production process by the Samdani Art Foundation.

In a country with an intense daily struggle, art comes out strong, but often remains ignored. In Bangladesh, we do not have any museum of contemporary art, or educational institutions shedding light on young artists' paths. The art institutions in Bangladesh are still teaching curriculum from the 1970s. If someone wants to travel abroad, the scholarships are too few and far between.

So when Diana Campbell Betancourt, the Artistic Director for the Samdani Art Foundation, told me about their recent edition, 'Samdani Seminars' which is aimed to open up new possibilities for art making and encourage cross-disciplinary communication and experimentation within Bangladesh, I felt hopeful. The program's intentions are to introduce local audiences to international practices in the hope to widen their artistic horizons and create future opportunities for local talent. And these are precisely the kinds of initiatives which can nurture promising artists.

I'm most excited, however, about the next Dhaka Art Summit due to be held 5-8 February, 2016. The Summit facilitates inter-generational and inter-regional dialogues that were not possible in the past, some because of the restrictions of movements of people and goods across South Asia. The cross-border approach that the Foundation has taken was long overdue for this region. Bangladesh was a part of India until 1947, and then Pakistan until 1971. We have Myanmar on one side and Bhutan up top. How can we deny the artistic melody our similarities and differences produce?

Going back to that conversation I had with artist Tayeba Begum Lipi, we discussed some of her past projects, one of which took place at the border of India and Bangladesh. As an independent initiative led by Lipi's husband Mahbubur Rahman, two groups of artists from both lands had set camp on each side of the border. They called the project "No Man's Land," as appropriate for the occasion. In that whole week spent at the border, the artists from one side were not allowed to communicate verbally with the other side, though they saw each other at work all day. On the last day the Indian and Bangladeshi artists were allowed to meet on the border for half an hour. Lipi recalled the enthusiasm with which they ran towards each other, embracing and sharing immense and unexpected love and performing impromptu pieces. "That was the best half hour," Lipi had told me with a faraway smile on her face.

[W]e deeply believe, in South Asia art is here to stay, and will be travelling beyond borders. In fact, it already is.

Looking from the outside, I believe artists for generations have been living in a no man's land -- the work of Bangladesh's Sultan preserved in Pakistan, Indian-born Satyajit's dialogues in the mouths of Bangladeshi children, or Bangladesh's musical legend Lalon Shah's or Swiss German Painter Paul Klee's influence on Bengal's Novel Laureate Rabindranath Tagore's work. The chain of events, the promoting hands, and the artists finding space, metaphorically or physically, where art can flourish, where artists can reach that rare moment of fulfillment, all that to me takes place in a no man's land, without mental or physical borders. Whether it is the government of West Pakistan, West Bengal's Chief Minister Bidhan Chandra Roy or Dhaka's Rajeeb and Nadia Samdani, who open the doors to limitless artistic journeys, pushing forward prolific talents towards their next big eclipse, we deeply believe, in South Asia art is here to stay, and will be travelling beyond borders. In fact, it already is.

Like Us On Facebook |

Follow Us On Twitter |

Contact HuffPost India

Also see on HuffPost:

-- This feed and its contents are the property of The Huffington Post, and use is subject to our terms. It may be used for personal consumption, but may not be distributed on a website.